NOAA is the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

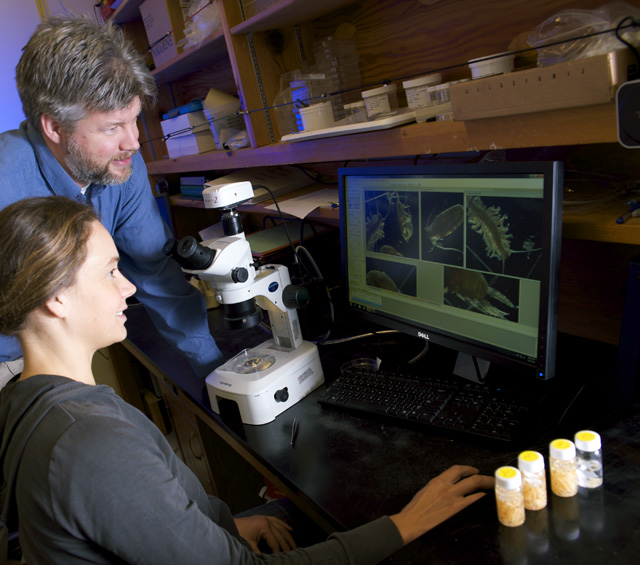

Through an ongoing series of oceanographic surveys on board the university’s research vessel Coral Sea and ongoing research at the Telonicher Marine Laboratory in Trinidad, HSU faculty scientists and students are collecting data that are considered essential to better-informed management of coastal fisheries and related resources.

“This is really new,” said Dr. Eric Bjorkstedt, who is leading the HSU operation. He is a research scientist with NOAA’s Fisheries Service and adjunct professor in the HSU Department of Fisheries Biology. “In conjunction with ocean observations off Newport, Oregon and the Bodega Marine Lab, we are starting to provide comprehensive data for the northern California current. In many ways it is the fisheries breadbasket of the California Current System.”

This is the first year Bjorkstedt and his colleagues been able to develop a comparative analysis across the northern California current and contribute the results to the annual CalCOFI report, titled the “State of the California Current.” CalCOFI is the California Cooperative Oceanic Fisheries Investigation. Download the State of the California Current Report here (PDF).

Bjorkstedt, who led this year’s report, said the observations off the North Coast greatly expand the report’s scope. Until recently, it was focused largely off southern California. The addition of North Coast observations has improved the understanding of regional variability in how the California Current responds to climatic events, like the recent El Niño.

Putting the past year’s ocean data together, Bjorkstedt and multiple co-authors concluded that the El Niño had a physical effect on the southern portion of California Current System, but not a significant biological effect. In contrast, anomalously warm conditions in the north appear to have had stronger biological consequences.

“For example, it may not have been a very good year for young salmon off the North Coast in Fall 2009 or heading to sea in Spring 2010,” Bjorkstedt said.

“Up here there was a much stronger dominance than usual of southern copepods—planktonic crustaceans—which tend to be small, accumulate fewer lipids (fats), and therefore are ‘energy-poor.’ The potential consequence is that the salmon may have encountered food sources that weren’t all that good, which can affect growth and survival.”

Bjorkstedt cautioned that other indices of survival have to be factored in. Scientists cannot yet determine conclusively if 2009-2010 was a good or bad salmon year.

Strategically, one of the main goals of long-term ocean observing is to develop ecosystem indicators to support fisheries management off the North Coast and along the California Current as a whole. “For example, we want to see how well observations off Newport correlate with the survival of Klamath River salmon,” Bjorkstedt explained. “Eventually, we want to be able to develop Klamath-specific predictions for, say, Chinook salmon returns several years out. Right now we’re beginning to examine whether the Newport Line data might be useful in the short-term, but in another couple of years, when we have five or six years of data, we can begin to do our own analysis to inform fisheries managers who are trying to predict salmon populations. The whole purpose of the effort is to support informed and effective resource planning.”

Operationally, the long succession of year-round observations will supply important information to fishermen. Strong predictions of a big harvest will enable them to take advantage of it. Forecasts of poor harvests will provide them crucial lead time to anticipate a lean season or an outright fisheries closure. As Bjorkstedt put it, “If a poor fishery looked likely for a given year, knowing that well ahead of time could help soften the surprise or shock factor, even if the economic impact couldn’t be mitigated all that much.”

What is clear at present—and confirmed again by the latest report of the California Cooperative Oceanic Fisheries Investigation—is that the California Current System is by no means homogeneous or uniform. “That means you can’t take observations from San Diego or Monterey Bay and use them for fisheries management off Oregon or the North Coast,” Bjorkstedt said. “The system must be viewed holistically. This ties in with NOAA’s mandate to develop comprehensive, integrated assessments of entire ecosystems, practical assessments that can support sustainable use of marine resources.”

In addition to the ship-based oceanographic observations, the latest “State of the California Current Report” includes for the first time observations on surface currents made with high frequency radar, including data from HSU-operated radars that are part of the California Ocean Currents Monitoring Program. Radar observations provide a valuable complement to traditional satellite-based remote sensing data and coast-wide buoy readings. Combined, they provide Bjorkstedt and his fellow researchers with insights into the intense dynamics of the California Current System.