Located in the rolling hillsides near the village of Crnobuki in North Macedonia, archaeologists are uncovering a lost ancient city with ties to one of history's most legendary leaders—Alexander the Great.

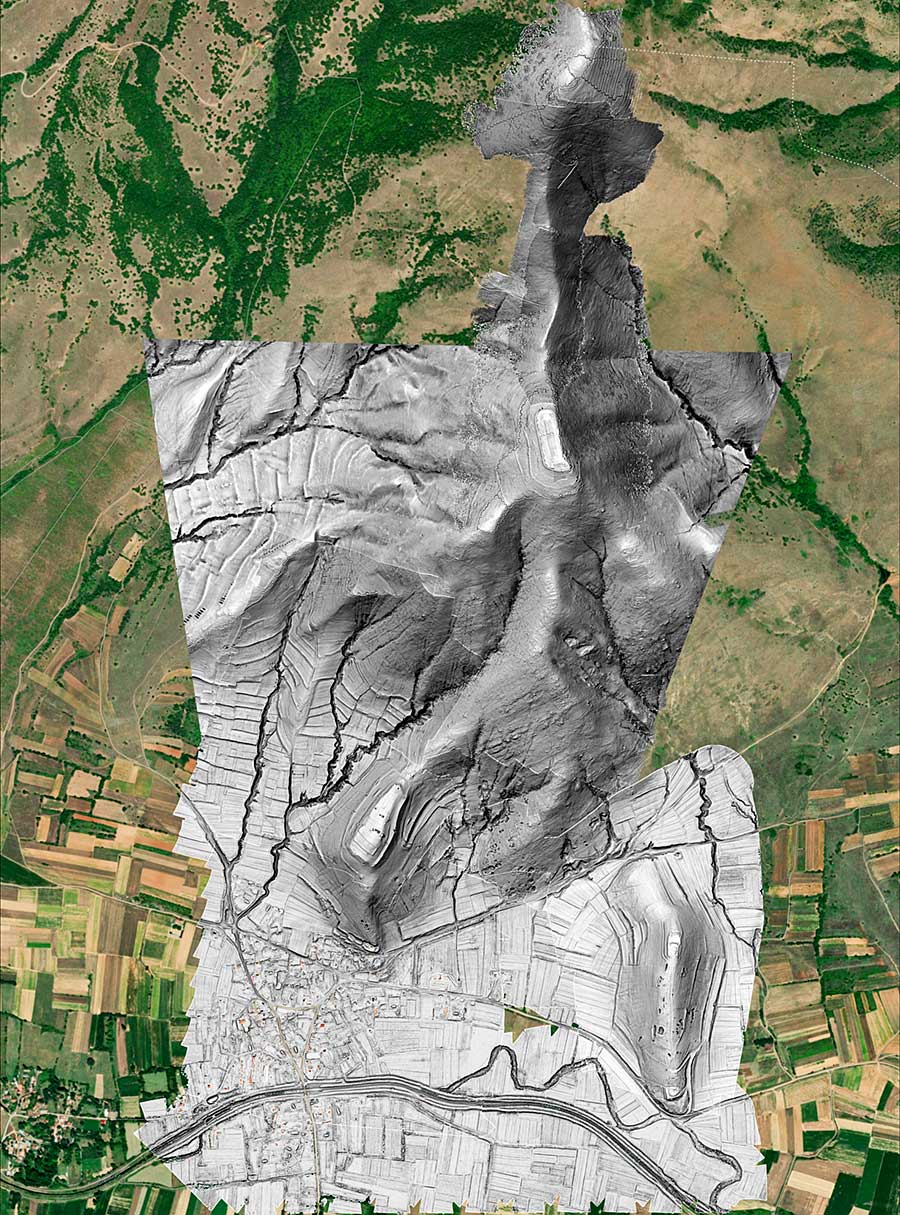

The site, known as the archaeological site of Gradishte, was once believed to be a modest military outpost. But recent research has revealed a vast acropolis that predates the Roman Empire by centuries, possibly even millennia.

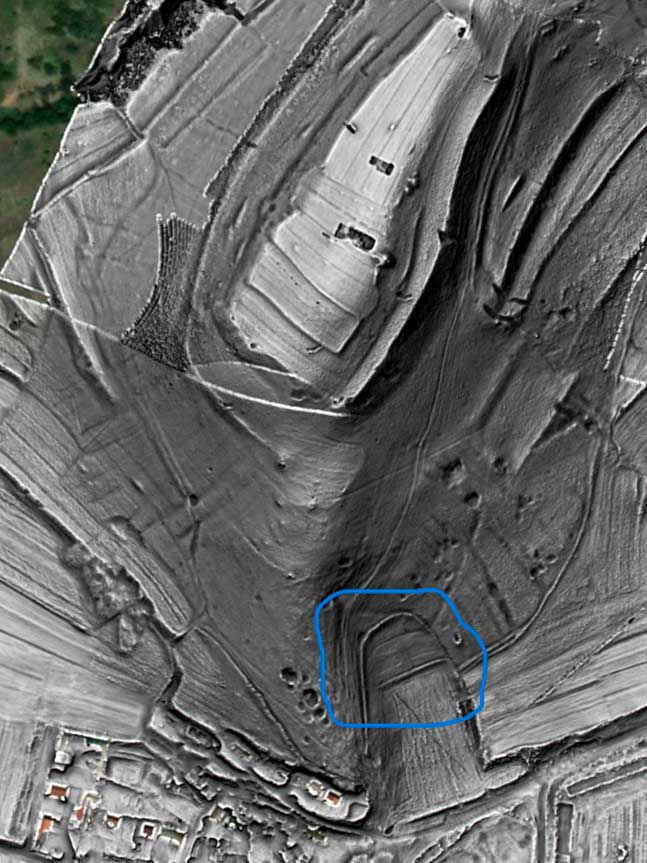

This discovery was made in 2023 after modern technologies—including ground-penetrating radar and drone-deployed lidar acquired with funding from Cal Poly Humboldt's College of Arts, Humanities & Social Sciences and support from the college's dean—revealed a once-thriving city that spans at least 7 acres. That's roughly the size of five football fields.

Cal Poly Humboldt researchers, including students, are playing a central role in this groundbreaking project. They are working with North Macedonia's National Institute and Museum–Bitola to unearth clues about the city's size, scope, and historical significance.

This is a once-in-a-lifetime discovery, explains Nick Angeloff, Cal Poly Humboldt Anthropology faculty and lead archaeologist on the project.

The project has attracted both national and international attention. This summer, Macedonian President Gordana Siljanovska-Davkova met with members of the research team, praising them for helping to preserve and record the site's cultural and scientific value on a global scale.

Angeloff believes Gradishte may be the lost capital of the Kingdom of Lyncestis, Lyncus. Lyncestis is an ancient settlement and hub for the Upper Macedonian Kingdom that was settled in the 7th century BCE—a hypothesis first made by archaeologist Viktor Lilcic in 2011. It's also possibly the birthplace of Queen Eurydice I, the grandmother of Alexander the Great. Queen Eurydice played a key role in shaping the political landscape of the region and securing the dynasty that would later influence the course of Western history.

"We're only beginning to scratch the surface of what we can learn about this period," Engin Nasuh, archaeologist.

But it wasn't just its inhabitants that made it significant; its location did, too. Situated along trade routes to Byzantium (later Constantinople, now Istanbul), Angeloff says it's also possible that historical figures like Octavian and Agrippa passed through the area on their way to confront Cleopatra and Mark Antony at the Battle of Actium (31 B.C.E.). That legendary battle set the stage for the rise of the Roman Empire.

Excavations here have so far unearthed artifacts that are further reshaping what scholars thought they knew about the site. One find in particular—a single coin—has proven especially significant.

To date this coin, Macedonian researchers analyzed its imagery and inscriptions, proving it was minted between 325-323 B.C.E., during Alexander the Great's lifetime. That discovery shifted the site's known origin back more than a century.

Minted at the Miletus Mint over 2,300 years ago (between 325-323 B.C.E) in what is now Türkiye, this coin was discovered at Gradishte in 2023 and is helping to rewrite the city’s timeline. Photos by Slave Stojanov.

But recent evidence suggests the site may be thousands of years older.

Newly discovered axes, a Venus figurine fondly named 'the Lady of Crnobuki', and fragments of ceramic vessels found at Gradishte suggest that humans began occupying it as far back as the Bronze Age (3,300-1,200 B.C.E.).

The project is opening a window into the history of the Macedonian civilization long before Alexander the Great, explains Engin Nasuh, curator-advisor and lead archaeologist at the National Institute and Museum–Bitola.

"We're only beginning to scratch the surface of what we can learn about this period," Nasuh says.

The ancient Macedonian state, one of the first modern states in Europe, had an enormous impact on the world, he explains. "It is a civilization that played a major role in today's understanding of the world and the desire to connect different civilizations and cultures."

The research at Gradishte is just one part of a larger effort to understand early European civilizations, Nasuh says. "I see it as a large mosaic, and our studies are just a few pebbles in that mosaic. With each subsequent study, a new pebble is placed, until one day we get the entire picture."

Working in sections, Humboldt researchers carefully excavate the site, removing dirt layer by layer with tools like brushes or picks, then sifting through soil for artifacts from coins to textiles to bones. Photo by Mark Castro.

Building a Trans-Atlantic Research Hub

That picture may be even more expansive than many realize.

"The excavations might provide unique archaeological insight into some of the greatest stories from the beginnings of history. Like the origin of the warriors who created the great Phrygian kingdom in Anatolia, the famous Pelagonian and Paeonian heroes who protected Troy in the Iliad, the founding legends of the Macedonian Argead dynasty, the Macedonian-Roman wars, the war of Caesar with Pompey, and many more." That's according to Ljuben Tevdovski, former Macedonian ambassador to Canada and theoretical researcher who's working closely with Angeloff to help shape a landscape scale research project.

Yet Gradishte—and other Macedonian archaeological sites—remain relatively under-explored. Tevdovski sees this as an opportunity, viewing the Humboldt-Macedonian collaboration as a cultural and academic bridge with the potential to uncover new stories about our shared past—and perhaps even our future.

Tevdovski sees the Humboldt-Macedonian collaboration as a cultural and academic bridge. One that has the potential to uncover new stories about our shared past, and maybe even our future.

"Learning about the local history, heritage, artifacts, and symbols provides a unique insight into the hearts and minds of another nation and region," says Tevdovski, who has been instrumental in expanding the project's international scope. "And doing it together with the locals—in teams of intellectuals, researchers, and students—creates a long-lasting bond between institutions, communities, and even entire societies."

The growing international partnership, which will soon engage both Macedonian and American students, provides multi-perspective understanding of societies, processes, and the world, he explains. "That's something we need now more than ever. It's the open-minded approach, the trust, the mutual respect, and the shared dedication to a common dream: building a transatlantic research hub that will help us better understand the past, nature, and the future of human societies."

Standing in a recently excavated area next to unearthed artifacts at the Crnobuki site, Nick Mavrolas ('25, Anthropology), a crew lead with Cal Poly Humboldt’s Cultural Resources Facility, uses a total station theodolite—an electronic tool that measures distance, slope, angles, and elevation—to record the precise location of a discovered object. Photo by Ocean Song Edgar.

Ancient Life Shaping New Opportunities

While the project sheds light on one of Europe's earliest civilizations, it's offering students and recent graduates hands-on experience in the field and in the University's Cultural Resources Facility (CRF).

Since 2023, Humboldt students have worked on the project under the guidance of the project's Principal Investigator (PI) Angeloff, and fellow Anthropology faculty and co-PIs, Instructor Barbara Klessig, CRF Director Mark Castro, and Co-Director Justin Carlson. They participate in excavations, artifact analysis, and more.

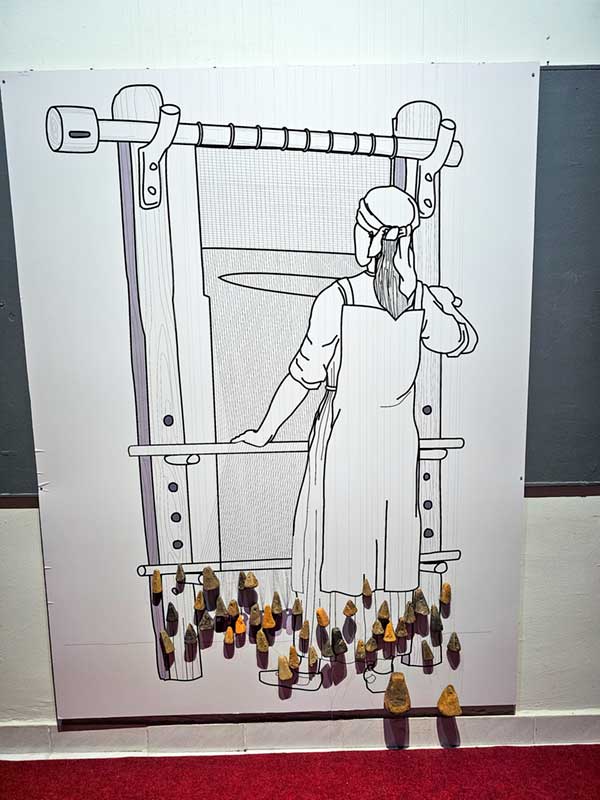

Nyah Hawkins ('24, Anthropology), research assistant at the CRF, is helping reveal more about the lives of the city's ancient inhabitants by studying materials like clothing.

“Textiles are definitely an overlooked aspect of archaeology, but I believe that it is one of the most important things to understand,” Hawkins adds. “Everybody, on all levels of society, had to be clothed, and what garments are made of can tell us a lot about the people who were wearing them, such as social status, their lives, and their occupations.”

Hawkins analyzes textile-related artifacts uncovered at the Gradishte site, particularly clay loom weights. Working alongside students and faculty in the Anthropology Department's Experimental Archaeology Lab, directed by Klessig, she's reconstructing the weights to better understand how they were made, used, and what they reveal about ancient technologies and trade.

Cal Poly Humboldt researchers help clean and catalog ceramics, most believed to be from vessels found at Gradishte, at the lab in Bitola, North Macedonia. The location and depth of these findings, as well as the quality and materials, give clues to the context and time period the ceramics were made and how they were used. Photos by Ocean Song Edgar.

"My goal is to determine where the clay, used in textile tools like loom weights, is coming from—whether it was sourced locally or imported," she explains.

She notes that the Roman Via Egnatia trade route passed nearby, increasing the likelihood that imported materials, including silk, reached the settlement, offering insight into the city's economic and cultural connections.

Jessica Morris ('25, Anthropology) has contributed to the Gradishte project since 2023. Now a student in Cal Poly Humboldt's Applied Anthropology M.A. program, she's building on the work she began as an undergrad. During the 2023 excavation, she cataloged finds, and in 2024 and 2025, she participated in excavations at Gradishte and another site in North Macedonia. She also performed soil analysis to reveal patterns about how the site was used over time.

Morris says the project has taken her learning beyond the classroom.

"I've learned so much from books and classroom settings, but this experience takes it further. You're zooming in on microscopic soil particles and then zooming out to the broader landscape—seeing how those interactions tell a bigger story," she says. "There's also the whole data recovery process, from using advanced tools to organizing large-scale projects. It's a totally different level of learning."

Morris's current research also focuses on textile tools uncovered at Gradishte, particularly clay loom weights. Working alongside Hawkins and Klessig, she reconstructs the tools to better understand how they were used and made. She recently presented this research at the Society for American Archaeology.

_CC.jpg)