Growth Market

HSU’s first-of-its-kind seaweed farm

By Mike Dronkers

It takes a diverse skillset to get a seaweed farm up and running in California waters. Permitting expertise, aquaculture scientists, governmental partnership, and the local harbor district all led up to the installation of HSU-ProvidenSea.

The team shoves off the dock just before sunrise. It’s low tide on a clear, brisk December day—the temperature has dropped into the 30s overnight, and the sun is still tucked behind the hills. This is the last day of finals, but more

importantly, it is harvest day.

The Humboldt State University seaweed crew is motoring across Humboldt Bay to the University’s new seaweed farm—the first of its kind in California—in hopes of kickstarting the state’s entry into a billion-dollar global industry.

“Seaweed farming is an industry that is about 500 years old,” says Rafael Cuevas Uribe, farm co-designer and HSU Fisheries Biology professor. “But this is the first time here in California that somebody’s doing red seaweed at commercial scale in open waters.”

The farm’s designers want to show how a versatile crop, linked with marine conservation and climate mitigation, can work in California.

The pilot project, called HSU-ProvidenSea, is a collaboration between HSU and GreenWave, an environmental nonprofit that helps coastal communities launch and scale regenerative ocean farms.

“We want to give future farmers a ballpark idea of what to expect, “ says graduate student Erika Thalman, whose master’s degree thesis is centered around this pilot project. Testing the waters of California’s regulatory and economic environment is a big part of the experiment. “HSU’s farm is basically the guinea pig for farmers and for the various agencies that have a say in the permitting.”

HSU-ProvidenSea grows Pacific dulse Devaleraea mollis (previously known as Palmaria mollis), a red seaweed found in Humboldt Bay. Sometimes called “the bacon of the sea,” it’s known for its umami flavoring. While rich in minerals, vitamins, protein, and antioxidants, this seaweed is much more than a superfood.

Fisheries Biology Professor Rafael Cuevas Uribe sows California’s first open-water commercial seaweed crop.

“When I tell people I have a seaweed farm for a thesis, they always ask, ‘What’s the market for it?’” says Thalman. “But they don’t realize how many products seaweed is already in.”

The nutritional benefits of seaweed are well documented, but dulse has found its way into everything from fuel to fertilizer. And with so many applications, seaweed could offer overfished marine communities a way to diversify revenue.

Alongside the economic benefits, seaweed is a very efficient carbon trap. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, “eelgrass, mangroves, and salt marshes are already known for their ability to store carbon. But seaweeds pull more of the greenhouse gas from the water than all three combined based on biomass.” That means seaweed farms can help to combat local impacts of ocean acidification.

Other benefits include water purification, removal of nitrogen and phosphorus, and creating habitat for marine organisms.

Aquaculture is already big business locally, with Humboldt Bay producing about $10 million in oysters and oyster seed. With infrastructure already in place, the seaweed team could follow the path of oyster growers.

“Our vision is to bring this new industry to Humboldt Bay, but we also want to be a leading example for the rest of California,” says Karen Gray, GreenWave’s California reef manager. The project is funded by the California State University’s Agricultural Research Institute and HSU’s Sponsored Programs Foundation.

Testing the waters

ABOUT ONCE A WEEK, Thalman boards a small boat at Woodley Island Marina in Eureka and motors out to the farm, which inconspicuously sits about a quarter of a mile offshore in a pre-approved aquaculture site across the bay from HSU. Other than its boundary buoys, you could kayak right by it and not know it’s there.

HSU-ProvidenSea doesn’t need much babysitting. But when it does, it’s a heavy lift. “Sometimes kelp drifts into the line, and I can tell you that moving wet kelp is a very good core workout,” says Thalman, laughing. “We have fun out there even if it’s raining.”

Other than clearing the lines, Thalman takes monthly seaweed samples that are analyzed for any contaminants the seaweed may be absorbing.

With students handling the day-to-day elements of the farm, they can monitor growth and troubleshoot problems as they arise. Their hard-wrought experience can be passed along to any future seaweed startups.

The farm’s design is simple, inexpensive, and scalable. “It’s a low-impact design that really works with the environment,” says Gray. The farm is mostly rope, suspended in the water column, with four anchors being its only physical footprint. “You don’t need fresh water, feed, or fertilizer. The seaweeds are growing with available nutrients and natural sunlight, and all it has to do is grow.”

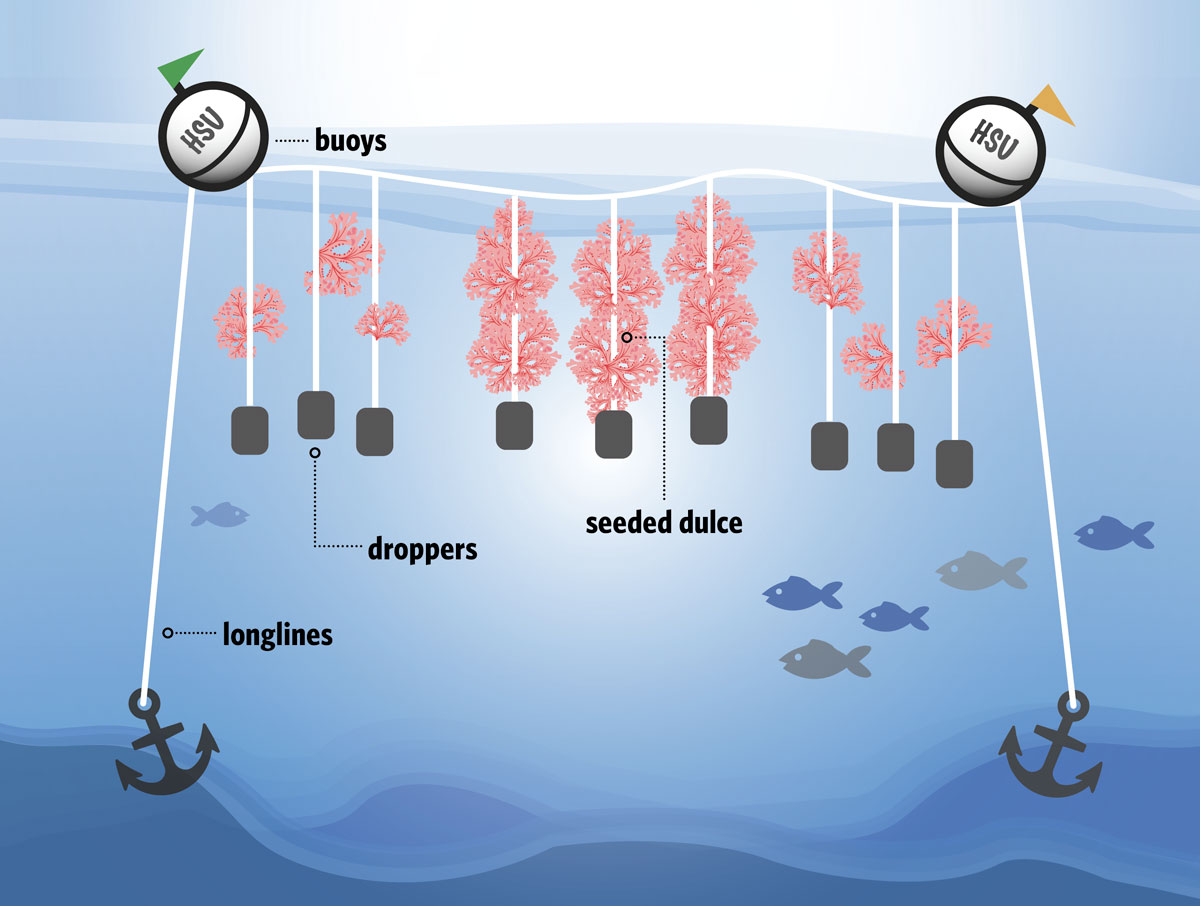

Its design relies on two 350-foot ropes, called longlines. Anchored at each end, the longlines are held near the surface by buoys. Shorter ropes called droppers dangle down from those longlines. The droppers are seeded with dulse grown at HSU’s Telonicher Marine Lab.

There’s a Goldilocks element to this kind of vertical farming: If the seaweed is too close to the surface, it gets sunburned. Too deep, and it can’t properly photosynthesize. One of Thalman’s scientific priorities is to study the best growth depth, so they seeded the droppers at one-meter intervals, starting at surface level, down to three meters deep.

At HSU’s Marine Lab, graduate student Erika Thalman (right) prepares Pacific dulse (Devaleraea mollis, previously known as Palmaria mollis), a red seaweed that HSU-ProvidenSea affixes to droppers in Humboldt Bay (left). Sometimes called “the bacon of the sea” and known for its umami flavoring, dulse is rich in protein, fiber, iodine, and potassium. It’s used in a wide range of products from meat substitutes to garden amendments.

VIDEO: Watch the HSU-ProvidenSea team install the seaweed farm at hsu.link/seaweedfarm.

Testing the waters

THE TEST CROP was a modest 25 pounds. “If we were a full-on commercial outfit, we would’ve loaded the lines all the way up, and let it go longer than four months,” says Thalman. But the proof of concept was the real harvest. “We learned that seaweed could be grown in Humboldt Bay.”

After the team took some samples for lab analysis, California’s first crop of commercially licensed seaweed had been harvested. Some of the harvest went to a local small business owner who was experimenting with soil amendments. The rest of the crop was donated to Trophic, an alt-meat startup.

Using early data, HSU-ProvidenSea is already shaping the next crop and its management. For instance, Humboldt Bay’s vigorous tidal currents loosened some of the seaweed, so Thalman is considering using mesh bags for the next batch. And as far as the Goldilocks depth, data show that three meters is too deep, and one meter is just right.

For now, the team is getting ready for the next crop. And with the seaweed market expected to top $12 billion by the end of the decade, HSU-ProvidenSea may be a key player in bringing this industry safely and sustainably to California.

The farm’s design consists of a longline suspended by buoys, anchored at each end. The rest is vertical farming, with seaweed suspended at different points in the water column from short ropes called droppers.