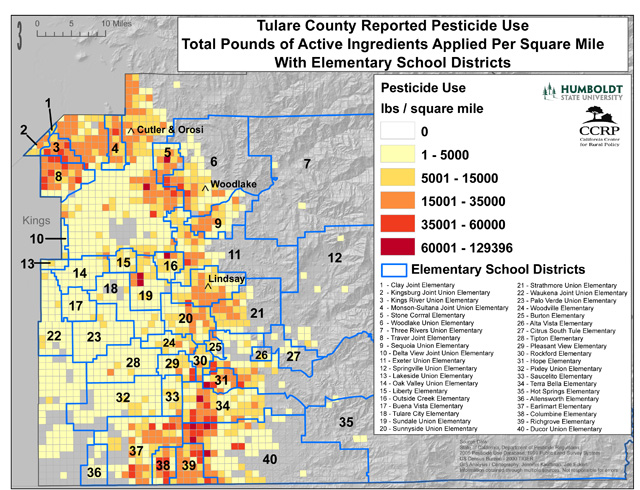

HSU’s recently-completed pesticide mapping project, funded by the California Endowment, centered on a novel combination of “socio-spatial” analysis and field research involving residents of six largely Latino communities in Tulare and Monterey Counties. Working closely with community networks among agricultural laborers, the HSU student/faculty team supported Tulare County’s adoption of buffer zones around schools and playgrounds. Aerial pesticide spraying is now banned in those zones.

“We interviewed community members who had been dismissed in the past as uneducated farm workers when they reported autism, unusually high rates of twin births and people sickened with asthma or migraines,” said HSU sociologist Sheila Lakshmi Steinberg of the university’s California Center for Rural Policy. “They told us their biggest concern was pesticide spraying around schools. We provided them with visual maps and technical assistance to trace pesticide applications. We gave voice to their concerns through our research.”

Sheila’s husband, Steven Steinberg, Director of HSU’s Institute for Spatial Analysis, explained, “The California Department of Pesticide Regulation issues data sets each year, but absent the knowledge to get access to them and analyze the information, the data aren’t meaningful to the general public. Understanding what pesticides have been used, and where, is buried in those data sets.”

http://now.humboldt.edu/images/uploads/pesticides.pdf" title="3.3mb">Download a PDF of pesticide use within elementary school districts in Tulare County

The Steinbergs and their student researchers unearthed nuggets of valuable information by bridging the digital divide. They gathered “socio-spatial” data, combining computer-generated maps with interviews that documented how agricultural workers are affected by pesticide drift. Environmental mapping of pesticide use and application rates was meshed with qualitative data—stories about community health.

Now farm laborers and their community leaders can visualize the data and pinpoint which pesticides they are looking for and the health risks they pose.

In the course of the study, the Steinbergs made a point of inquiring how their academic research could be of practical benefit to community members and policy makers. Workers agreed overwhelmingly that spreading the word about pesticide use was paramount.

One community member highlighted the urgency of the situation, saying, “The Central Valley is a cup, so no air moves. I have family members who are suffering now. There is no time to waste, anything we can do to move forward.”

The pressing need led to the publication of an easy-to-use flier in both Spanish and English about the toxic chemicals in pesticides. The handout, being distributed across multiple communities, summarizes the precautions to be taken against exposure. It alerts parents, for example, that children spend a lot of time on floors and other surfaces, exposing them to dangerous residues lying on playgrounds or tracked into houses. The pamphlet also provides information about the many symptoms triggered by pesticides and how to report pesticide drift. It is titled, “Your Life, Your Family and Your Community: Protect Them from the Pesticides Around Us.”

The Steinbergs learned from their interviews that awareness of the risks must be shared at all levels of the farming community because many laborers do not speak English. As one resident said, “Farm workers don’t understand. The crew boss needs to be informed. Most people just go to work and don’t realize the consequences for coming in contact with pesticides.”

Likewise, another worker noted, physicians diagnosing symptoms do not always take pesticide exposure into account. “Health care providers need to encourage ongoing trainings that help workers to recognize the symptoms of pesticide exposure,” the laborer said. “They hear me coughing and assume I have a cold.”

The Steinbergs believe their socio-spatial project can serve as a model for communities up and down the state, while providing essential knowledge to policy makers, legislators and environmental activists for regulatory reform.

“This is really a hallmark research project of social and environmental justice,” Sheila Steinberg said. “It enables both poor laborers and upwardly mobile Latinos to make hands-on use of applied research and improve their lives.”

The impact has been tangible. One worker observed, “We found out that over half the schools in Tulare County are within half a mile of a field.”

Alma Martinez of Radio Bilingue in Fresno said California Rural Legal Assistance, Cultivo Consulting and Radio Bilingue used the maps in a pesticide drift presentation in the three rural Tulare County communities of Cutler-Orosi, Lindsay and Woodlake. “When the residents were able to see the amount of pesticides being applied and how close they were to their children, they were shocked,” Martinez recounted. “Most of them knew pesticides were being sprayed, but being confronted with the data was the spark that set them into action.”

In the wake of the community presentation, two farm worker action groups have emerged in Cutler-Orosi and Lindsay. “The groups are drafting action plans for solutions to the pesticide drift problem,” Martinez said. A Tulare activist pointed to one approach: encouraging farmers to employ alternative growing methods.

Nine undergraduate and graduate students in natural resources, GIS, psychology, English and sociology contributed to the report about the HSU project, “People, Place and Health: A Socio-spatial Perspective of Agricultural Workers and Their Environment.” It can be downloaded at the namesake Web site http://peopleplaceandhealth.org/. The Web site is available in Spanish at http://www.gentelugarysalud.org.

The report contains these policy recommendations and findings:

• State law should require prior notice of pesticide use on properties adjoining school grounds as well as on school grounds.

• A centralized database should be created of accessible pesticide information.

• Buffer zones should be established around sensitive sites.

• Better research is needed of exposure resulting from wind drift and pesticides carried by dew. Drift findings should be disseminated widely with improved communication protocols.

• Night-time spraying heightens pesticide drift and increases exposure to communities that adjoin farm land. This should be taken into account in regulatory reform.

• Data about pesticide and fumigant applications are usually not available until well after the fact, typically several months to a year later, when the state’s annual reports are released. Although it may not be feasible to disclose every pesticide use in advance, applications near schools, hospitals, nursing homes, day care facilities and neighborhoods should be relatively simple to report. It would encourage the exercise of basic precautions, like closing windows and wiping clean playground equipment.

Humboldt State’s California Center for Rural Policy and Institute for Spatial Analysis collaborated on the pesticide mapping project with the Agricultural Worker Health Initiative, which is funded by the California Endowment and includes Poder Popular, an advocacy group for farm worker communities across California./

Dr. Sheila Steinberg can be reached at 707/826-4563; Dr. Steven Steinberg at 707/826-3202; and Connie Stewart, Director of Research for HSU’s California Center for Rural Policy, at 707/826-3402.