The study presents the first conclusive evidence that tree twigs in conifer trees like pine and fir can not only absorb water directly through their surfaces, just like roots and leaves, and maybe even quicker. This discovery could reshape how scientists understand tree hydration and forest health, especially as climate change increases drought and cold-weather stress.

“We really went down the rabbit hole with this one, with one experiment after another,” said Chin. “We didn’t just want to show that twigs drink rainwater—we chased one lead after another until we figured out how they do it, where it goes, and why it matters.”

Until now, most studies focused on how leaves absorb water, but Chin and her team wanted to know what happens when a raindrop hits a twig. Using a series of cutting-edge experiments, they discovered that young conifer twigs like those from pine and fir trees can absorb large amounts of rain very quickly due to tiny capillary pores on their surfaces. Once inside, the water moves through the twig’s outer tissues and into its inner core, or xylem, the part of the plant that usually carries water up from the roots.

But unlike roots, twigs can take in rain that has not reached the soil, offering trees a valuable secondary source of water. That’s especially important during droughts when any rain might be brief and light or after freeze-thaw cycles, when the tree's normal water pathways may be blocked by air bubbles (called embolisms) that form inside the xylem.

To fully trace how water gets into twigs, the researchers ran five separate experiments:

- Isotopic labeling showed that rainwater absorbed by twigs moved not only into the twig itself, but also up into leaves and down toward the trunk, even when those areas were sealed off from rain.

- Water absorption tests measured increases in twig weight and internal water pressure, confirming that significant amounts of water were taken in during simulated rain.

- Fluorescent dyes helped trace the exact paths water took inside the twig, both between cells and through them.

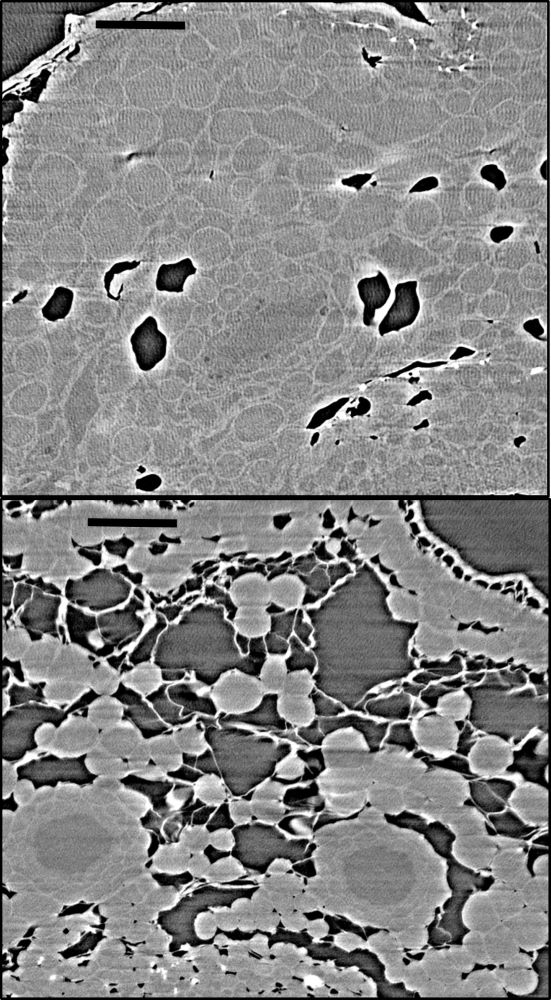

- MicroCT imaging provided high-resolution X-ray views of water entering the twig’s pores and collecting in internal spaces like the cortex and pith, areas that act like natural reservoirs.

Thermal imaging revealed that water spreads incredibly fast over the twig surface, sometimes uphill, thanks to tiny pores and capillary action, allowing remarkably quick capture of light rain.

Water absorbed by twigs is stored in what is normally the airspace.

The research shows that twigs are not just passive distributors of water—they actively participate in acquiring it and store it in surprising ways. This hidden ability could be crucial for tree survival in harsh environments.

Understanding how twigs absorb rainwater gives scientists new tools to predict which trees are better equipped to survive climate change, which could inform real-world forest management and conservation strategies.

But there’s a flip side: the same traits that help trees absorb water could also lead to greater water loss during hot, dry conditions. That makes it even more important to understand how different species use (or lose) water through their twigs.