“These creatures are part of a recovered ecosystem following a major extinction of fish groups at the end of the Devonian Period, so it’s a time of incredible morphological diversity in cartilaginous fishes, including all kinds of weird anatomy we don’t see in modern sharks,” says Cal Poly Humboldt Biology instructor Allison Bronson (‘14, Biology, Zoology), the lead author of the new study.

The new species, Cosmoselachus mehlingi, lived 326 years million years ago and is named after Carl Mehling, senior museum specialist for the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), who has worked in the AMNH’s Paleontology Division for 34 years.

“He’s supported dozens of Museum paleontology students over the years. But he’s also a person with a deep appreciation for the strangest and most enigmatic products of evolution. We’re delighted to honor him with a weird old dead fish,” Bronson says.

The genus name—Cosmoselachus—was given for Mehling’s nickname “Cosm,” to recognize his “contributions toward the acquisition and identification of numerous fossil chondrichthyans, as well as his indefatigable enthusiasm for all unusual vertebrates and many years of service to paleontology.”

Bronson, along with colleagues from the AMNH, the University of Florida, and Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle in France, focused on a fossil specimen collected in the 1970s by Royal and Gene Mapes, a husband-and-wife team of scientists and professors at Ohio University whose collection was donated to the AMNH in 2013.

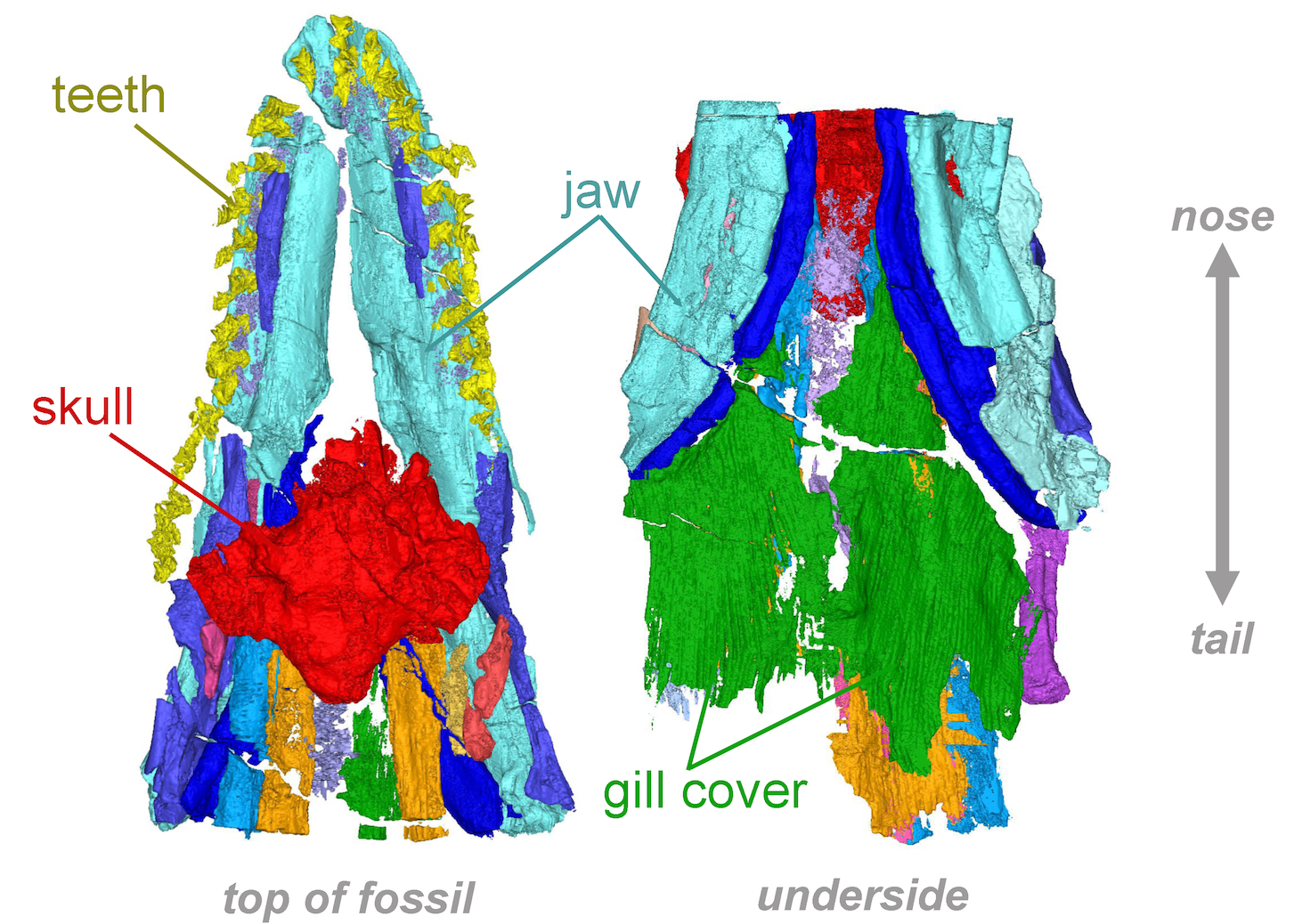

That fossil specimen, Cosmoselachus, was CT-scanned at the AMNH and digitally reconstructed at the AMNH and at Cal Poly Humboldt. The team worked for many months to describe its anatomy, including dozens of tiny pieces of cartilage.

Once the reconstruction was complete, researchers placed the specimen in the tree of life of early cartilaginous fishes, finding that it plays an important role in understanding the evolution of an enigmatic group called the symmoriiforms.

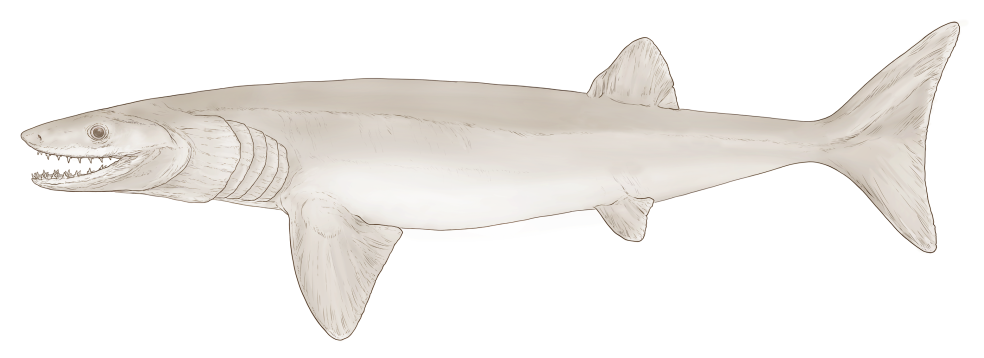

This group has alternately been linked with sharks and ratfish, with different researchers coming to different conclusions. Cosmoselachus has mostly sharklike features, but with long pieces of cartilage that form a gill cover, which is only seen in ratfish today.

Cosmoselachus is one of many well-preserved fossil sharks from the oil-bearing Fayetteville Shale formation, which stretches from southeastern Oklahoma into northwestern Arkansas and has long been studied for its well-preserved invertebrate and plant fossils.

Bronson and her coauthors focus much of their recent research on fishes from this formation because of the fossils’ exceptional preservation and their position in time.

At Cal Poly Humboldt, Bronson teaches classes in Biology and Fisheries, including Evolution, Zoology, and an Advanced Ichthyology course this semester focused on Sharks and Rays. “We have such a strong program in organismal biology here at Humboldt. I feel very lucky that I can share the details of this research with my students. They not only understand all the concepts, but are also genuinely interested in learning about fishes,” she says.

With respect to the fossil’s new name, Bronson says, “lots of us are in science because, basically, we love to learn new things and work with our friends. It feels wonderful to be able to name a species after someone who has done so much for his fellow paleontologists.”