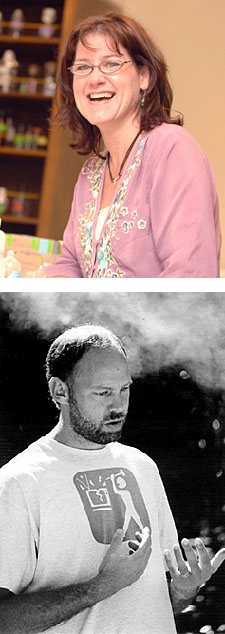

The husband-and-wife research team specializes in the study of extremophiles--organisms that thrive in the planet’s harshest environments. They met in 1993 at a research laboratory where Wilson was studying microbes that help break down pollutants and Siering was investigating the role of bacteria in wetlands.

“It was love in the lab,” Siering says.

The couple’s extreme dedication to extremophiles has paid off. The microbiologists are part of a team that recently won a $1.2 million National Science Foundation grant to study the microscopic organisms that live in the boiling, acidic lakes and hot pools of California’s Lassen Volcanic National Park, west of Redding.

The project, a venture with Portland State University and California State University-Chico, will fund studies by graduates and undergraduates that will delve into the diversity and abundance of extreme microbes in Lassen. Siering and Wilson have access to $543,000, with the remainder of the grant going to the other schools.

The team will use a remote-controlled boat built by Portland State students to collect samples from Boiling Springs Lake—a sulfurous, 25-foot-deep, rotten egg-scented body of scalding water. Students will study what types of extremophiles live in different parts of the lake, and how they interact. To increase public understanding, students will produce a brochure to explain Lassen’s extremophiles for park visitors.

There is a “cool factor” with extremophiles, which inhabit corners of the planet where other life forms are unable to persist due to extreme temperatures, pressure, salinity, radiation, acidity or alkalinity, Wilson says. Some live on scorching hydrothermal vents at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean, while others hang in caves and feed on sulfur. Some grow in temperatures up to 250 degrees Fahrenheit while others thrive in Antarctic ice.

“Maybe it’s a guy thing, but I wanted to study organisms that live in boiling acid,” Wilson says of the microbes that live in Lassen. “That’s extremely extreme.”

Extremophiles are important because they “provide clues to the limits of life,” Siering says. “How can something live in permafrost, or two miles below the surface, or on nuclear reactors?” These tough creatures also provide insight into the potential for life on other planets. Astrobiologists speculate that extremophiles could exist in the permafrost of Mars or the subsurface oceans of Jupiter’s moon Europa.

Extremophiles have practical applications for humankind. Some eat oil and other toxic substances, making them valuable in helping to clean up hazardous waste. Medical researchers consider extremophiles a potential source of cures, and some countries such as Japan are investing heavily in research to discover industrial applications for these tough creatures.

Extremophiles also provide insight about the origins of life on Earth. Billions of years ago, the planet was an inhospitable cauldron of poison gases and toxic substances. Extremophilic bacteria are believed to have sprung to life in this environment, helping to produce atmospheric oxygen that permitted the evolution of higher organisms such as plants, animals and humans.

“Bacteria get a bad rap,” Wilson says, “but most don’t cause diseases. In fact they are beneficial and are the basis of all ecosystems.” Wilson looks forward to learning more about the extreme bacteria that inhabit the hot pools of Lassen. “This work is really about learning about the roots of life on the planet,” he says

Like plants that live on the Earth’s surface, some extremophiles feed on carbon dioxide and produce organic carbon needed by other organisms. But while plants extract energy through photosynthesis, a process fueled by the sun, extremophiles, which often live in total darkness, rely on chemosynthesis. This process allows them to use inorganic molecules such as hydrogen sulfide or methane as an energy source.

Wilson and Siering, who work in side-by-side offices in the Biology Department and have a dog named Puddinhead, have no problem balancing work and home life, though “we did have to make ground rules about when we could talk about work,” Siering says.

Siering was hired in 1998 and Wilson worked as a lecturer until 2004 when he was hired as an assistant professor. Siering began brainstorming projects to study Lassen’s extremophiles while flying out for her job interview. Lassen Volcanic National Park—a five-hour drive from Arcata--is home to the largest hot spring in North America, and it is a great resource for HSU students, she says.

Siering was so excited about the prospect of teaching at HSU that she turned down a job at Johns Hopkins, one of the nation’s most prestigious research facilities. She and Wilson had visited Arcata previously and had great memories of the area’s high quality of life.

“We made a choice to come here. This was our dream place, and we have been very happy with our decision,” Siering says.