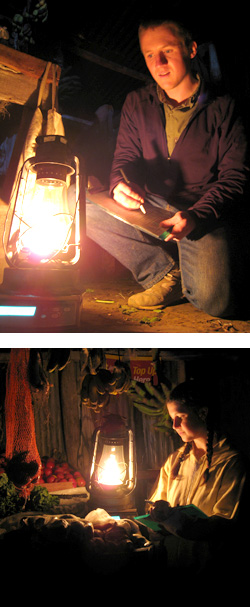

For about 25 cents a day Kenyan vendors can light their market stalls with kerosene lamps. This may sound like mere pocket change, but the cost is a major expense for the vendors, especially when the cost to light the stalls has tripled in the last two years. In addition to being pricey, engineers like Johnstone and Radecsky suspect that kerosene poses a health hazard.

Professor Dustin Poppendieck, of the Environmental Resource Engineering Department, explains that kerosene, like most fuels, gives off particulate matter when burned. In places were electricity is limited or not available burning fuel for lighting and cooking can be a dangerous source of indoor air pollution.

“Worldwide 1.6 billion people use fuel-based lighting and $40 billion is spent annually on fuel. Thirty million Kenyans use kerosene as a lighting source, that’s 80 percent of Kenya’s population,” said Poppendieck.

On the roof of the Science Building, Poppendieck and his research assistants, Environmental Resource Engineering undergraduates James Apple, Ryan Vicente, and Annie Yarberry, have replicated the typical Kenyan market stall. Together they have collected data on the amount and size of particulate matter present when different types of kerosene lamps are burned.

“We are trying to determine the health benefit of reducing vendors’ exposure,” Poppendieck explains. “Although they may only be exposed to it for three hours a night that is still significant.”

The risks associated with the lamps, which are generally located close to the vendor’s mouths and noses, posing an additional hazard, include upper-respiratory irritation and infections, lung cancer, asthma, allergies, and bronchitis. The lamps even emit ultrafine particles that are so small they may be able to pass though the air sacks in our lungs and enter the blood stream, said Poppendieck.

Environmental Resource Engineering Professor Arne Jacobson, a Schatz Energy Research Center Co-Director and the leader of the effort in Kenya, is teaming with Johnstone, Radecsky, and Poppendieck and his students. Collectively the research team is trying to calculate the health risk of kerosene lamps in open-air markets and the economics of switching to an alternative solution: Light Emitting Diodes or LEDs. The Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory is also a partner in the research.

“The primary goal is to quantify the economic and health benefits and show the World Bank, LED manufacturers and others why they should jump start LED lighting market in the developing world, in hopes that Kenyans can skip over incandescent light bulbs and go straight to LEDs,” Poppendieck said.

In the United States LEDs are commonly used for flashlights, auto headlights and in homes because they have a long lifespan and take very little energy to power.

Jacobson has been traveling to Kenya for ten years to conduct solar and LED research but this summer was the first time he brought students with him. “It was really exciting to be able to take grad students to the field. They brought a new level of enthusiasm and excitement to the work.”

Before traveling to Kenya, Johnstone and Radecsky, along with fellow employees at Schatz, spent hundreds of hours designing and assembling 20 LED lamps. Each LED contains a data logger, designed by engineers Kyle Palmer and Scott Rommel, of Schatz, that keeps a record of when people use the lamps.

Once there the Humboldt research team, along with their Kenyan research partner, Maina Mumbi, monitored the kerosene lamps of vendors selling vegetables, meat, milk, prepared food, and household goods. Walking around the marketplace, Johnstone and Radecsky worked with each vendor to determine how much fuel was consumed.

An important goal of the research is to understand the specific use patterns of Kenyan night-market vendors. By knowing this, engineers can make recommendations to manufacturers who design lighting products specifically for customers living in locations similar to Kenya. For example, if the results find that the majority of vendors charge their LED lamps at a charge shop for 30 cents per charge, engineers may recommend a design with batteries of greater capacity, allowing the customer to use the lamp longer before recharging.

The research team spoke to vendors about using LEDs instead of kerosene lamps and sold a little more than a dozen SERC manufactured LED lamps at a market-rate price of $10. Mumbi also sells solar panels in the hope that for another $10 vendors can let the sun power their new LED lamps. If not utilizing the sun, vendors can charge their LEDs via the electrical grid from the vendor’s home or charged at a charging station, similar to a gas station but for electrical appliances.

Radecsky said, “The vendors were as interested in us and the information we had to offer as we were in them and the data they were helping us to collect.”

Kenyan school children, in addition to vendors, learned about the economics of LEDs from the Schatz researchers. Johnstone and Radecsky gave a presentation to the Maai Mahiu Secondary School’s Environmental Club about the pros and cons of each lighting option. Students imitated Johnstone and Radecsky’s research by weighing lamps and analyzing the economics of kerosene lamps versus LEDs.

For Johnstone, the trip was a great opportunity to see another part of the world. Playing the part of researcher was more interesting than that of a tourist, he said.

Both Johnstone and Radecsky said that best part of the trip was working with the people who participated in the study. Johnstone described the vendors as “friendly, welcoming and interested in our research. It was rewarding to be immersed in their culture.”

As a gift to the vendors who participated in their research, Johnstone and Radecsky took photos of the vendors and gave them a copy. Each portrait was labeled with, “Off Grid Lighting Project 2008, Humboldt State University, Asante Sana,” which is Swahili for thank you very much.

This is also important work from a social justice perspective, Johnstone explained. “Our study aimed to provide good information about how people are using both fuel based and LED lights to provide insight on the environmental, economic, and health impacts of lighting technology. We found that many LED products are likely better for people than kerosene lighting,” he said. “They tend to be less expensive in the long run to own and operate, and do not emit dangerous particulate matter.”

Radecsky added, “[With the research results] we can make recommendations to manufacturers who design lighting products so that they can deliver better lights to customers living in locations like Kenya."

Johnstone will return to Kenya in late autumn as a researcher to conduct follow-up surveys with the vendors and further refine the LED project.