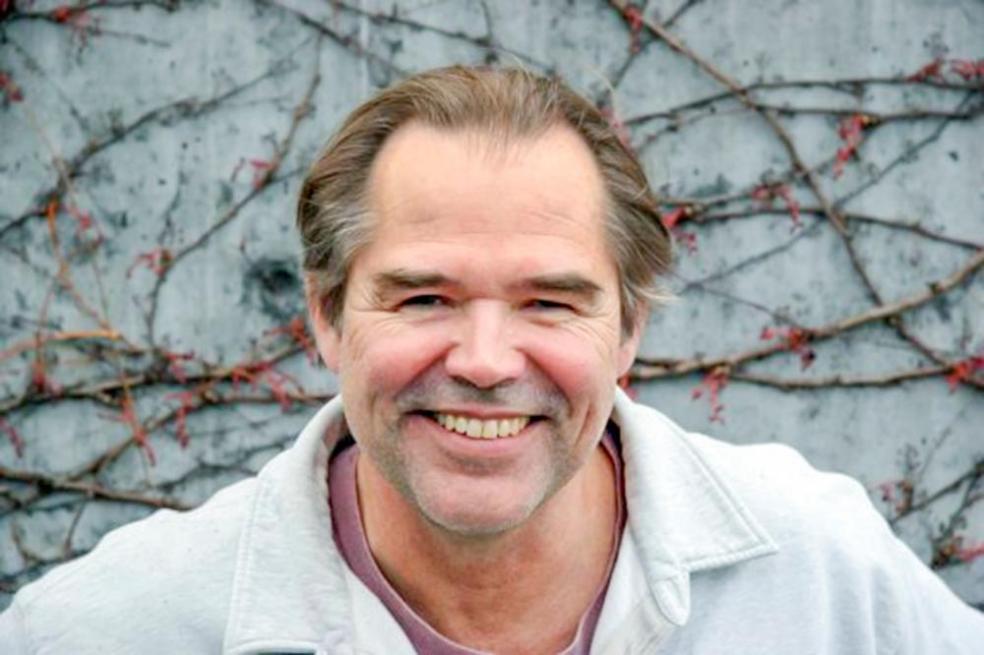

A fisheries biologist with a 39-year career conducting Sea Grant research, Edward Melvin (‘80, Fisheries Biology) is widely recognized as a global leader in seabird conservation. Melvin’s development of techniques to reduce bycatch, the untargeted marine species killed by commercial fishing gear, has been internationally recognized for protecting endangered species. In 2015, Melvin and his team were awarded the prestigious United States Fish & Wildlife Service Presidential Migratory Bird Federal Stewardship Award.

After retiring from the Washington Sea Grant at University of Washington last year, Melvin reflects on how his career on the high seas started at Humboldt State University.

Growing up in New York, Melvin fostered his love of the water while working as a lifeguard during the summer. After graduating from the University of Pennsylvania in 1974, Melvin got excited about the idea of living in rural Northern California and moved across the country to attend graduate school at HSU. During his time in Arcata, Melvin spent hours in the Wildlife & Fisheries Building stockroom, where he worked handing out binoculars and gear.

“It was an opportunity to get to know a real cross-section of both faculty and the student body,” says Melvin, who remembers the warm welcome he received at HSU. “The fisheries, wildlife, and oceanography departments were a tight little community. It helped me build confidence in my field skills and ultimately, launch my career.”

“Academia was demystified by personal experiences at HSU,” remembers Melvin. “It was fantastic. I didn’t want to leave!”

Melvin’s graduate thesis looked at different species of “off-bottom” oyster cultivation in the Humboldt Bay. Prior to the 80s, dredging, or “bottom-culture,” was still the dominant method of oyster aquaculture, which was decimating the native eelgrass beds that migratory seabirds depend on.

“Off-bottom oyster cultivation was just coming online,” says Melvin, who was the first person to grow different species of oysters in different habitats in the Humboldt Bay. The oyster industry took note of his research on water quality and yield: Melvin’s thesis data was used to establish an off-bottom cultivation operation on the Mad River Slough.

After graduating in 1980, Melvin was hired by the California Sea Grant and started working with commercial fisheries in Monterey Bay. At the time, boats were killing an unsustainable volume of by-catch, including seabirds and sea otters. Melvin served as a neutral liaison between government regulating agencies and the industry, which prepared him for future work in the salmon gillnet industry, where he found solutions to seabird bycatch that threatened to close fisheries in the Puget Sound.

After taking a position with the Washington Sea Grant, Melvin relocated to Seattle and spent the last 20 years of his career working with commercial fishermen in Alaska to prevent the mortality of endangered albatrosses and petrels.

“The tension between regulatory agencies and the fishing industry created a gap where I could be effective,” says Melvin, who has been recognized for developing techniques that have reduced by-catch in Alaska’s fishing industry by more than 90%. As seabird conservation went from a local issue to a global movement, Melvin got involved in international working groups that eventually took him to South Africa and Japan.