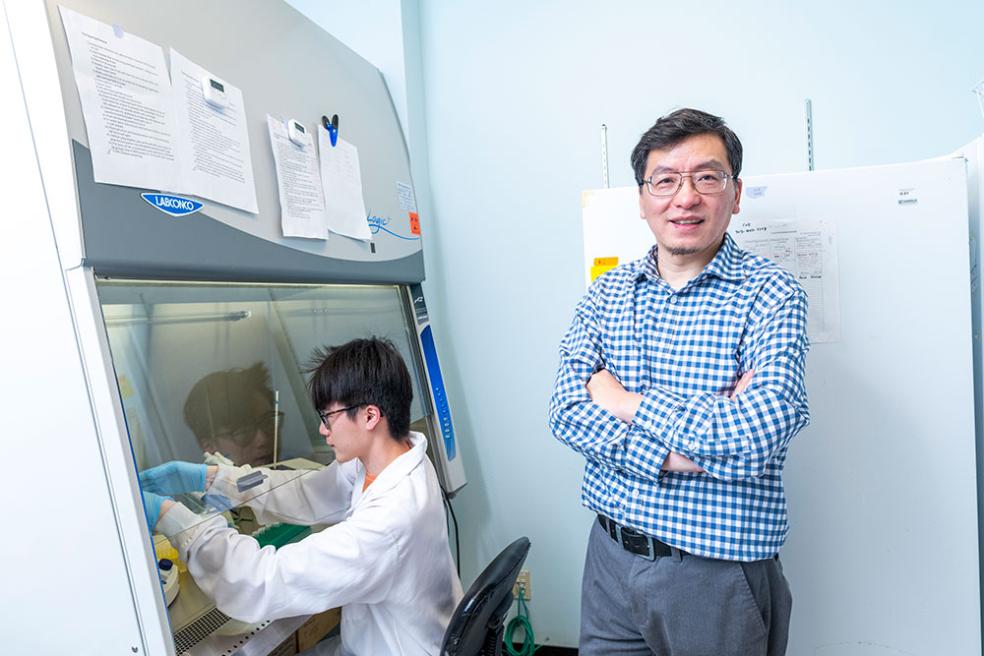

Biology professor Jianmin Zhong is working alongside students in his tick research lab to learn more about a novel bacterium found in certain varieties of ticks. The research team, which includes both undergraduate and graduate students, is investigating the bacteria’s ability to cause disease. What they learn may help uncover treatment options and reduce the rate of infections.

The team is examining the potential pathogen, Rickettsia species phylotype G022, in Western black-legged ticks. The ticks, which are spread across the Pacific West Coast from Washington throughout California, are the most common human biter in these areas.

A Western Black legged Tick. As part of the research, Zhong and his students are analyzing tick DNA, and blood from mammals to detect the bacteria’s presence.

Though Zhong first identified this bacteria more than a decade ago, little is known about it. However, some Rickettsia bacteria are known to cause illness, such as Rocky Mountain fever and typhus.

By studying this particular bacteria, Zhong’s lab is learning more about it, and whether or not it infects humans and other mammals. “Our research aims to understand the bacteria so we can eventually help diagnose, treat, and prevent those tick-borne pathogens,” Zhong explains.

The National Institute of Health’s (NIH) Support for Research Excellence SuRE Program awarded Zhong’s lab a grant for $590,000 to conduct the study. The funds will support student research.

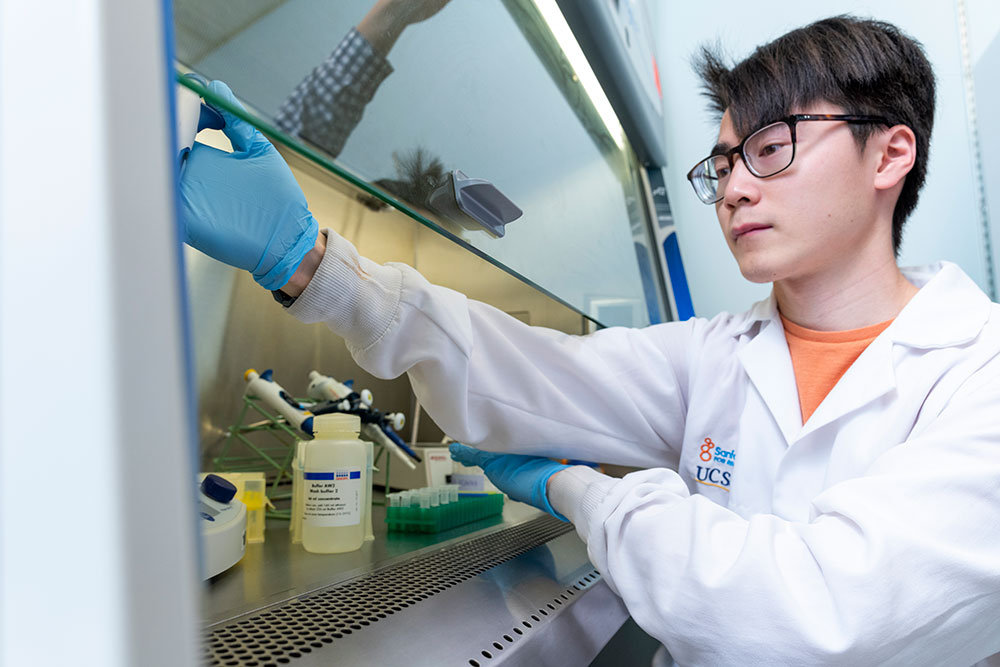

Oh Kwon’s research begins with DNA extraction. Within a biosafety cabinet, he cleans and dissects Western Black-Legged ticks, storing them in a -20 C freezer. When he’s ready, he then extracts and analyzes the tick cells for any bacterial DNA.

The research team is currently collaborating with the California Department of Public Health and the Center for Disease Control (CDC).

Ticks are second only to mosquitoes as vectors of disease in humans and carry thousands of potential pathogens that we have yet to fully understand.

According to research, the pathogens ticks transmit are a growing burden for human and animal health worldwide. For example, cases of Lyme disease, which experts estimate are grossly underreported, are on the rise. In fact, some studies have shown that Lyme disease diagnoses increased by more than 300% since 2016.

Thanks to a growing body of research, and factors like climate change—which is expanding the range of ticks—researchers have identified more and more bacteria in ticks, Zhong explains. This motivates his lab to find emerging diseases and new pathogens.

Zhong’s lab is compiling much-needed research on tick-borne diseases, explains Oh Kwon, a Biological Science graduate student and researcher in the lab. “Being able to see not only the route of transmission of these bacteria but also seeing which mammalian species are most susceptible will benefit our communities from a public health perspective.”

“There is still much to be done concerning our knowledge on vector-borne microorganisms, and I hope to be able to contribute to this field,” Kwon says.

As a Humboldt County local, Kwon is all too familiar with the arachnids and their potential to cause harm.

“My family frequently visited the redwoods and brought our dogs to walk through the natural foliage, but we always had to check for ticks,” says Kwon. Although his family has not experienced tick-borne diseases, he’s aware of individuals who do contract them, sometimes fatally.

Research shows that diagnoses of tick-borne illnesses, which peak in summer months, have increased by 60% in rural areas in the past seven years, according to FAIR Health, a nonprofit that has tracked these illnesses for more than a decade.

Fellow Biological Sciences graduate student and lab researcher Nicholas Woronchuk says the lab’s research is particularly important for rural communities.

“Because so many tick-borne diseases haven’t been characterized yet, regional severity may be worse in one area or another. But physicians don’t really know that, so it adds a layer of difficulty to diagnosis.” However, Woronchuk explains, “due to their proximity to tick habitats, rural communities are more susceptible to tick-borne illness and may experience more frequent exposure. Additionally, rural communities tend to lack widespread healthcare, which can result in undiagnosed tick-borne illness.”

Zhong has studied ticks for more than 20 years. “It's so amazing that a small body can carry so many pathogens and parasites,” he explains. “They affect our daily life; humans are exposed to the ticks, the ticks carry pathogens, and it is considered a public threat.”

His previous research on deer ticks investigated the life cycle of the arachnids, and revealed that a form of Rickettsia bacteria helps create folate, which is essential for living organisms, and helps ticks survive between meals. Similarly to the current research, results contribute to the understanding of tick biology and controlling populations in an effort to prevent, diagnose and treat tick-borne illnesses.