“We’re trying to understand the dynamics of clean energy adoption for people in off-grid areas and the factors that influence their ability and choice to invest in something that gives them better energy services,” says Arne Jacobson, director of HSU’s Schatz Energy Research Center.

Anecdotal evidence of off-grid lighting solutions for developing countries suggests an “energy staircase,” in which some first-time buyers of small solar-powered products (i.e., solar lanterns) eventually buy larger and more expensive home systems while often also keeping the old technology.

“It’s like product stacking rather than product substitution,” says Jacobson. “People who might buy a solar-powered device don’t necessarily get rid of their kerosene lamp. On a cloudy day you still want to make sure you have something for light.”

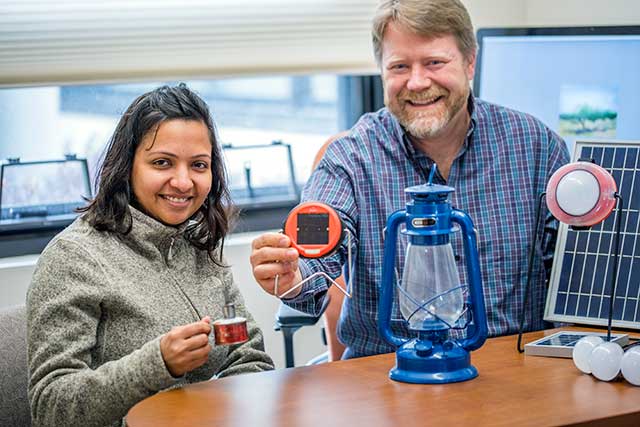

Through a $150,000 grant from the United Nations Capital Development Fund’s CleanStart Programme, Jacobson and his Schatz Lab team—which includes visiting scholar Richa Goyal and research engineer Meg Harper—will put the energy staircase theory to the test.

Over the next year, they’ll use a random sample of hundreds of off-grid solar product buyers in Uganda to examine if, how, and why customers buy these products and services. The findings will be released in 2017.

Understanding the buying dynamics can help Ugandans access technology that’s cleaner, better quality, safer, and healthier.

Currently, 85 percent of the population doesn’t have access to electricity, and kerosene lamps are the most common form of lighting. Kerosene, however, can be hazardous. The fuel can cause fires and is poisonous. In fact, a leading cause of poisoning for toddlers in sub-Sahara Africa is accidental ingestion of kerosene.

Besides major environmental, safety, and health benefits of green devices, the research will shed light on the basic issue of household economics.

“Ugandans have money, but the cost of kerosene—which is often about 10 cents each day—adds up pretty quickly,” says Jacobson. “Can they put enough money up front to buy an $8 solar powered lamp that pays itself back, and saves money, in a short period of time?”

The answer may lay in mobile-based payment options, which benefit countries like Uganda, where 85 percent of the population uses formal and informal financial services, 52 percent own a mobile phone, and mobile banking is the primary form of banking.

Currently, most solar-powered devices are bought with cash. For pricier devices that range from higher-end lamps (about $25.00) to home systems (about $250) that power multiple lights, some consumers turn to mobile banking to access microcredit loans or pay-as-you-go plans, spreading payments over time.

One example of mobile money at work is the payment system in Kenya. According to a report by “60 Minutes” most Kenyans use cell phones, and they don’t have access to a conventional bank account or grid electricity.

To purchase things like a solar-powered device, they make a small payment up front via cell phone and then continue paying a few cents per day. A payment activates a chip via a mobile phone connection that turns on the device. If the owner doesn’t make a payment, the chip doesn’t activate. The main company behind the technology, Safaricom, makes a profit off the fee it charges per transaction.

Part of HSU’s research is studying whether payment mechanisms like this help consumers move up the so-called staircase and buy better devices.

The findings could provide companies insight for designing better products. They might include a built-in mobile phone charger and the ability to pay via digital wallet and, in turn, increase sales.

It’s a win-win for both company and consumers. A built-in charger eliminates the 25 cent-cost local shops charge for recharging a phone. Better access to mobile banking means access to banking services with interest rates lower than those charged by informal financial networks. And higher sales mean profits for the company.