These inconspicuous documents, however, contain the work of linguist Li Fang-Kuei. The information, nearly a century old, may hold the key needed to complete efforts to sustain the Wailaki language.

As part of her Undergraduate Research and Creative Activity Fellowship with the Department of Anthropology, Hurtado is part of a team creating a digital archive of the notebooks. In addition to scanning and digitizing the original collection, the team will transcribe the information to the best of their abilities. The resulting information will be made available to scholars through the Bancroft Library at the University of California at Berkeley. Hurtado also plans to present this documentation to local tribes.

The Wailaki people are the descendants of the southernmost Athabaskan tribe of southern Oregon and northern California. Today though, there is no federally recognized Wailaki tribe and, according to Victor Golla, the language is basically extinct except for re-learners studying the language from notes.

Golla is a professor of Anthropology and Native American Studies at Humboldt State. He is also an expert on American Indian languages including the Athabaskan language, Hupa. In this line of work, it’s not uncommon to see the winding paths languages take to survive.

Perry Lincoln is another student on the team documenting Li’s notes on Wailaki. “Those people that kept language alive were the people who slipped through the cracks,” he says. Lincoln is of Wailaki descent and a member of the Round Valley Indian Tribes, a federally recognized confederation of tribes, which includes the Wailaki. In the Cultural Resources Facility, Lincoln is transcribing Li’s delicately written notes into a lasting digital archive. His interest in American Indian languages led him to Golla four years ago. But Lincoln could recall a time when tribal languages didn’t merit much concern or attention.

“I didn’t think of language as being ‘lost,’” he says. “My wife’s mom and dad both spoke Hupa and so did a few other elders.” But as the generation of fluent speakers aged and passed away, Lincoln realized how quickly a language could be lost. “Within one generation. That fast.”

While languages can be nearly wiped out in as little as one generation, it took almost 100 years and a circuitous journey for the notebooks containing the documentation of the Wailaki language to make their way back to the Pacific Northwest. It’s a story that begins with a Chinese linguist in the 1920s.

Li Fang-Kuei studied linguistics in his native China. As a graduate student at the University of Chicago in 1927, Li traveled to northern California to study the American Indian languages of the Mattole and Wailaki. It was thought at that time that these Athabaskan languages were historically related to Asiatic languages, and would therefore share tonal aspects.

Wailaki is a descriptive language, which Li documented through stories and questions that elaborated on the grammar used in the stories. Wailaki speakers would sit with Li, while he transcribed, pausing now and again to clarify. For instance, if someone mentioned a running horse, Li would pause to ask for the translation if it was plural, if the horse was stationary, if the horse was female if the horse was young. He would then ask questions about how to use the phrase in other tenses or in different conditions.

By the time he finished his research, Li wasn’t able to find support for the claim that tone was an important aspect in Mattole or Wailaki. However, his five student notebooks contained detailed notes on the linguistic structures of the languages. “If we only had one chance to document the language, we’re very lucky it was Li,” Golla says. “He allows us to understand the grammar and not simply vocabulary. That alone puts it heads and shoulders above other sources.”

By 1937, Li returned to Beijing to teach. His work on the Mattole language was published as part of his Ph.D. dissertation in 1930 with the University of Chicago. Before he could publish his documentation of Wailaki, however, Japanese advance troops had begun to create tension in China, especially around universities. Just ahead of World War II, Li fled China and returned to the United State, bringing the Wailaki notebooks with him.

“These notes were unpublished and irreplaceable,” says James Roscoe, director of the Cultural Resource Facility. “He got them out.”

Upon returning to the United States, Li found a position at the University of Washington in Seattle, teaching Chinese. It wasn’t until Li retired to Hawaii in the 1970s that academic interest in the Wailaki notebooks was revived.

During his retirement, Li continued to lecture at the University of Hawaii where he met two young, enthusiastic students with an interest in American Indian languages. “You had an elderly teacher and two eager undergraduates interested in an unfashionable subject,” Golla says. “They became a close-knit group.”

One of those students, William Seaburg, was interested in archiving and librarianship. With Li’s help, he was able to secure a position with the University of Washington to organize and archive the collection of noted linguist Melville Jacobs for the Jacobs Foundation. Before he left for Seattle, Li also entrusted Seaburg permanently with the Wailaki notebooks.

Seaburg earned his degrees in Anthropology and Librarianship and later became a tenured professor at the University of Washington. Still, he kept the notebooks in his personal possession until he and Golla, a professional colleague, decided the notebooks should be brought to Humboldt State.

“Bill said he’d like to see the notebooks made available to people interested in working with these languages,” Golla says. “But neither of us could think of a safe way to transport this valuable, absolutely unique material. Can you imagine if it was lost in the mail?”

The problem was resolved last December, when Jamie Roscoe volunteered to drive to Seattle and take personal charge of the manuscripts. Now safely in the CRF office, under lock and key, Hurtado and her colleagues are working them with on a daily basis. The letter of transferal signed by Seaburg grants Professor Golla legal custody of the Li materials until HSU's digitization project is finished. After that, arrangements will be made to house the originals in the Bancroft Library or some other permanent archive with an extensive collection of materials on California Indian languages.

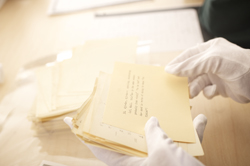

During their sojourn in Arcata, the Li notes are being looked after according to the highest standards of manuscript curation. The delicate, yellowed pages are now being stored in pH neutral envelopes and were handled with special gloves to protect the paper from acids found in skin oils as Hurtado and others created the high resolution, archival quality scans. In addition to the notebooks themselves, Hurtado is documenting the notecards that contain Li’s original, preliminary analyses of the structure of the Wailaki language. Currently, she, Lincoln, and fellow student Nikki Martensen are among those transcribing the contents of the notebooks and notecards into digital documents.

While Hurtado’s ultimate goal is to preserve the historically and culturally significant documents, Lincoln’s ultimate goal is to secure revival. “My dream is to have a class teaching whatever we can find.”

“Documents aren’t the language; they just document it,” Golla says. “But for American Indian languages in general, this collection is very good. People could create a new use—a revitalization—of Wailaki from these notebooks. And that is significant to people, because part of reviving language is redefining who you really are.”