This data will have many applications, including understanding how vegetation regenerates after fires, and how plant communities are being affected by a drying and warming climate. In the long term, this project will advance regional understanding of climate change.

“The Klamath Mountains are home to more than 3,500 vascular plant taxa, making it one of the most botanically diverse places in North America,” says Forestry Professor Lucy Kerhoulas (‘06, Botany, ‘08, MS Biological Sciences). Kerhoulas co-leads the study alongside other University faculty including Geography, Environment & Spatial Analysis Chair Rosemary Sherriff and Biological Sciences Chair Erik Jules.

The project aims to document and map the botanical diversity. The maps produced from these data will be the most comprehensive maps of plants in the Klamath Mountains, Jules says.

The project is funded by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. It is conducted in partnership with the California Native Plant Society (CNPS), the project lead, and the Bigfoot Trail Alliance.

The Klamath Mountains range is vast, spanning 19,000 square miles from Northern California to Southern Oregon. This project is focused in California only; it will conduct 1,600 vegetation surveys—each at a different location—and collect hundreds of specimens for the next three years.

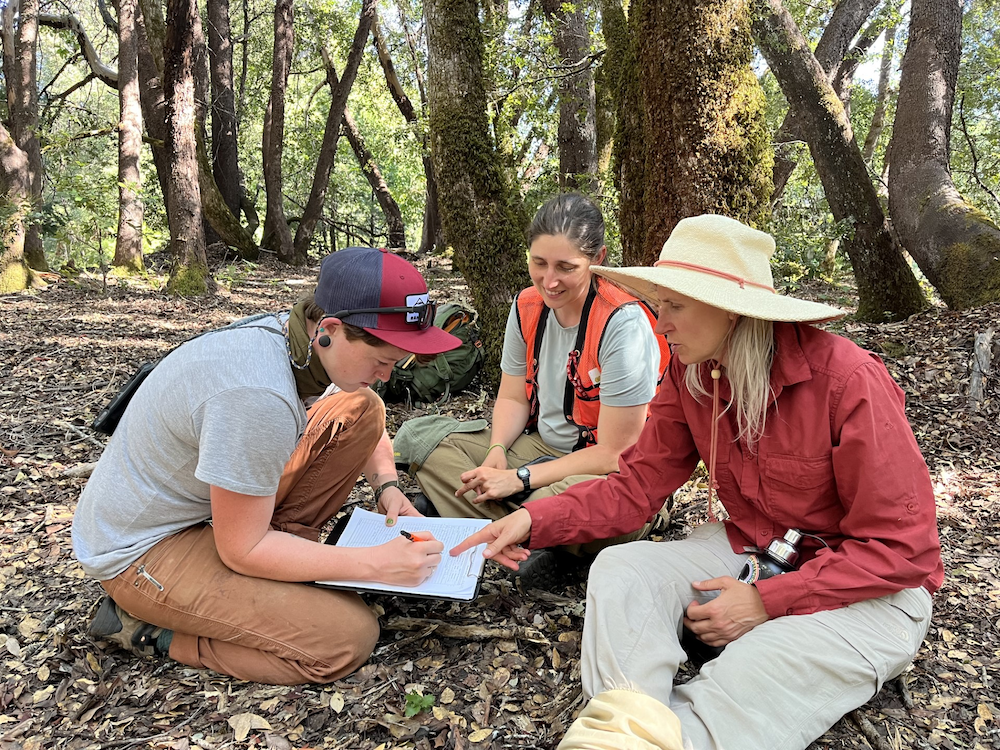

Surveying began this summer, and researchers—who include both graduate and undergraduate students—are on track to complete 500 surveys by the end of this year.

As part of these surveys, researchers will visit sites throughout the Klamath, documenting all the plants they encounter with a focus on vascular plants. They will then create a species list of all trees, shrubs, grasses, and forbs (herbaceous plants that aren't grasses). Much of the plant samples they collect will be donated to the University’s Vascular Plant Herbarium—one of the largest in the California State University system with more than 105,000 specimens.

The region and its plants vary greatly, explains Julie Evens (‘00, MS Biology), vegetation program director at the CNPS. “The variation can be seen from the western slopes that receive over 80 inches of rain per year and support a rich assemblage of over a dozen conifer trees, to the eastern edge of the range that receives less rainfall and includes high-desert plants like western juniper.”

The information collected will provide an incredibly rich dataset on the region’s biodiversity, Evens says. “It will assist land managers in guiding restoration and other management decisions. Since the survey data provides a current reflection of the habitats across the Klamath mountains, they will provide land managers with restoration palettes from the more pristine areas sampled and will pinpoint locations experiencing threats from invasive species or other disturbances.”

Documenting the botanically-rich region will have myriad impacts, says the project’s co-lead and ecologist Michael Kauffmann (‘12, MA Biological Sciences) of the Bigfoot Trail Alliance, a nonprofit dedicated to protecting the Klamath Moutain’s Bigfoot Trail. “Because the Klamath Mountains hold one of the most biodiverse temperate forests on Earth, it’s important to know what is here, how expansive vegetation stands are, and if any threats are encroaching within particular vegetation communities.”

Kauffmann’s specialty is in the Klamath Mountains and its plants. He has traveled through the mountains over the last 25 years and knows them inside and out. This has allowed him to identify areas for researchers to go and collect data.

There are so many parts of the study that are exciting to Kauffmann, but what stands out the most are the students, he says. “It’s inspiring to work with up-and-coming botanists and ecologists from Cal Poly Humboldt, relearning the landscape through their eyes, and training them to be the future stewards of the Klamath Mountains.”