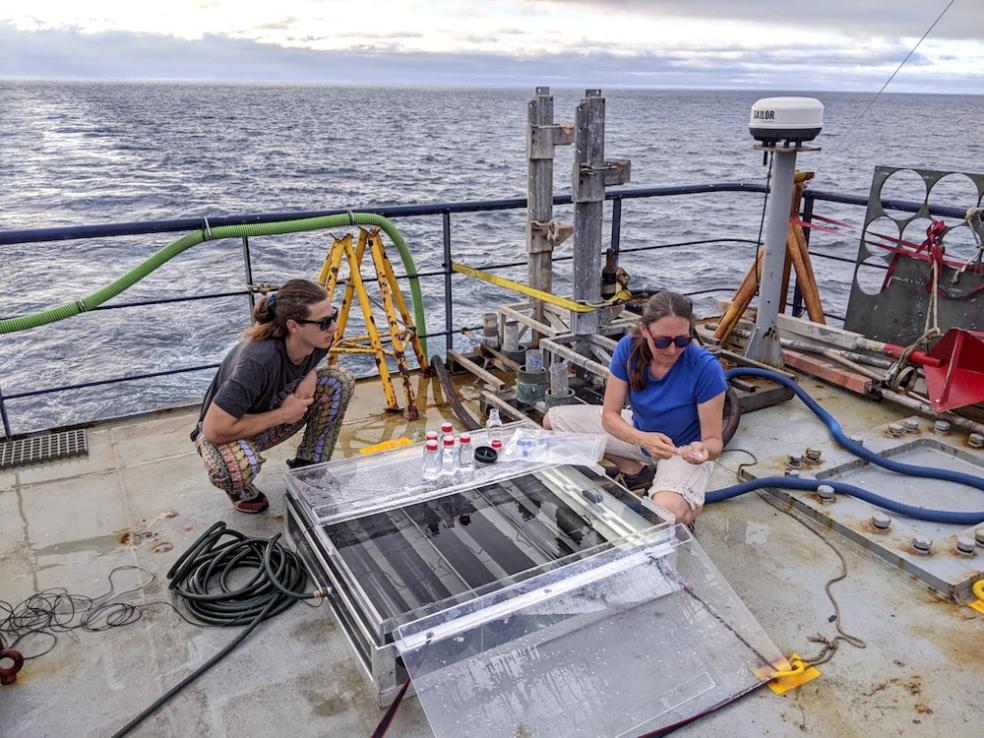

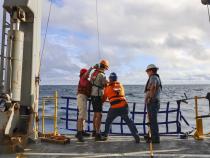

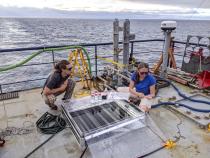

But before that daily burst of life begins, members of Humboldt’s Trace Metal Team are already at work on the deck of the “R/V Marcus Langseth.” Using a winch, they lower GoFlo bottles—specialized containers to collect water samples without contamination—into the sea. They seal them shut at depths of up to 300 meters to capture water before the light wakes the phytoplankton. By 8 a.m., while most of the ship’s crew heads to breakfast, they’ve already logged hours of sample collection. In the afternoon, they begin the process again, finishing by dinner—a routine they repeated for three weeks.

Chemistry faculty Claire and Ralph Till, and Microbiology undergraduate student Noah Schuhmann embarked on the three-week research cruise this August to the Galápagos, where they joined an international team dedicated to understanding the region’s oceanography. The data they collect will help scientists better protect marine life in a changing climate.

The project is led by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s (UNC-CH) Adrian Marchetti and Harvey Seim, who are working closely with the Galápagos Science Center, and researchers at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, North Carolina State University, University of Victoria, and Cal Poly Humboldt.

This summer’s expedition builds on more than a decade of research aimed at understanding how ocean nutrients reach the ocean’s surface and impact phytoplankton communities.

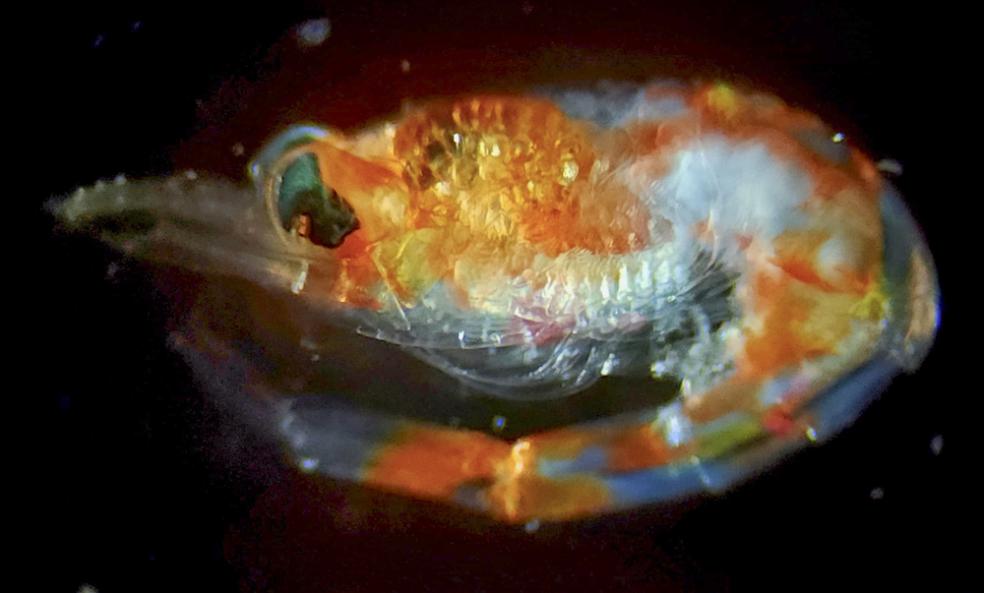

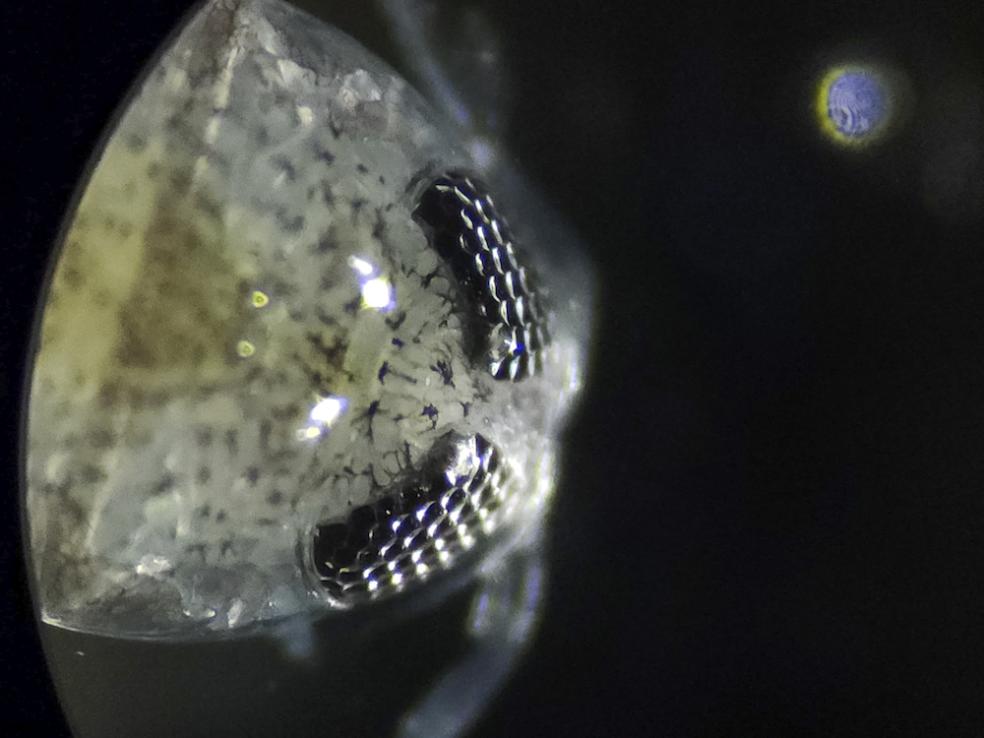

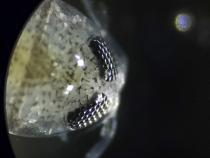

These microscopic plants are the foundation of the ocean food chain. “They can only grow in the light, so nutrients at the surface of the water are key for their ability to grow,” says Claire Till.

The Humboldt Chemistry Trace Metal Team—which consists of the Tills and Schuhmann—is zeroing in on one micronutrient: iron.

“Iron is an essential micronutrient, required in small quantities for plants and animals [to survive],” Claire Till explains. “In roughly one-third of the surface ocean, lack of iron is what stops phytoplankton from growing more.”

Every morning and afternoon, the team—whose participation in the research was made possible with support from the California State University Council on Ocean Affairs, Sciences & Technology (COAST)—collects seawater samples from different depths to measure the concentration of iron. The findings will help reveal how nutrients travel through the water and ultimately shape the entire marine ecosystem.

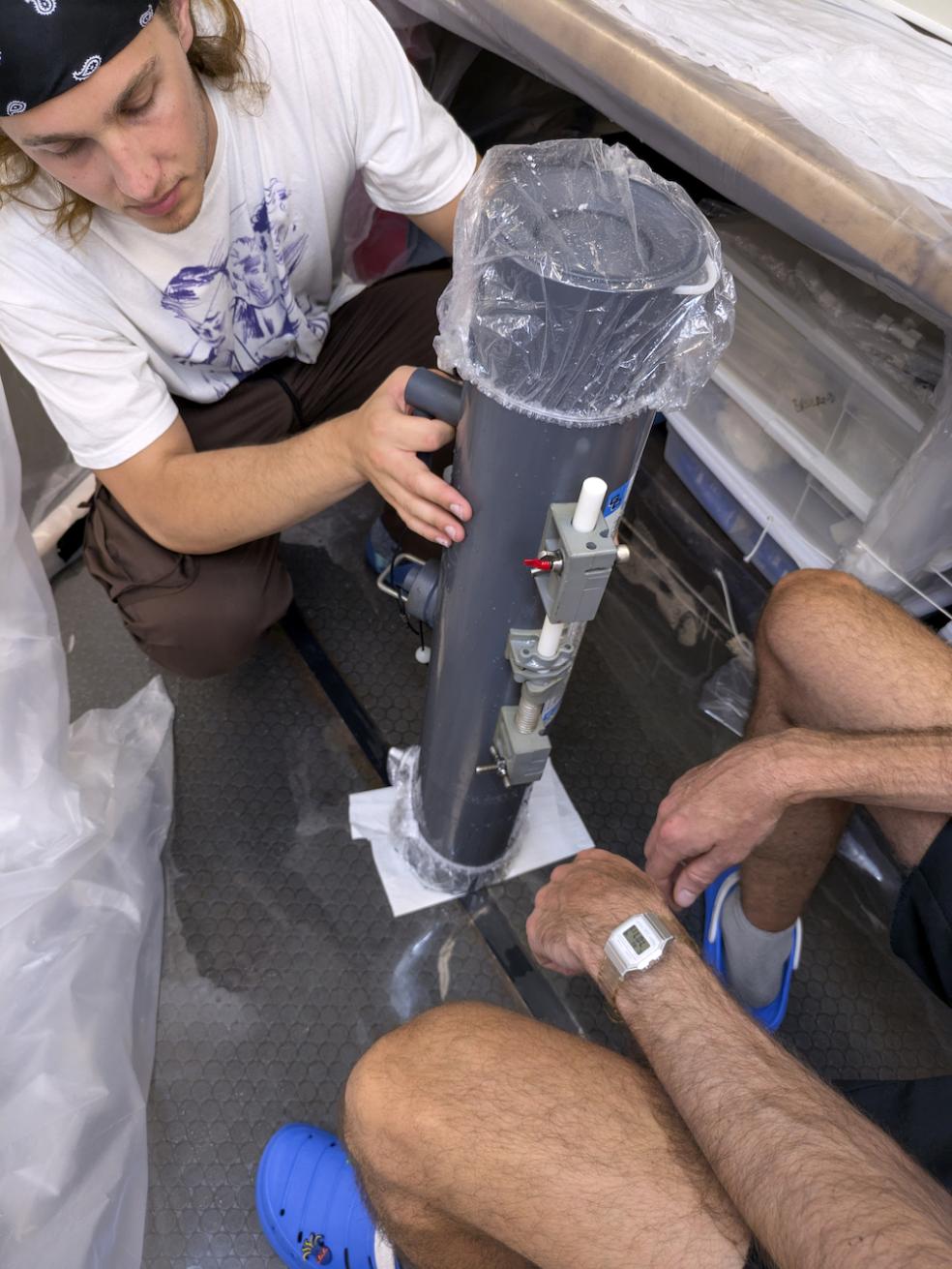

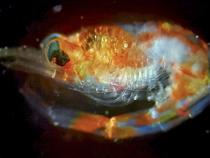

Collecting the samples is a delicate task. Because even the ship’s rusty metal surfaces could contaminate them, the team constructed a plastic “bubble” cleanroom. Inside it, they filtered, froze, and preserved samples to further analyze at their lab at Cal Poly Humboldt over the next year.

For Schuhmann, being aboard the “R/V Marcus Langseth” with students and scientists was transformative.

“The difference in experiences among the students, post-docs, and professors has been striking to me in terms of the paths they took to get where they are,” he adds. “I have learned much—in such a short time, it seems—that had not been clear to me before this cruise, even as an upcoming fourth-year student,” he says. “As someone questioning whether grad school is the right path, this experience has been invaluable in helping me understand what that might mean.”

The experience immersed Schuhmann in science, giving him skills that will be valuable no matter what career path he pursues, says Claire Till.

Even amid their rigorous schedules, the team also experienced moments of quiet wonder, between sailing by volcanoes and sightings of whales, flying fish, and squid.

Now back on land, they’ve returned with more than 400 seawater samples ready for analysis. Those samples will help reveal how nutrients move through the ocean and sustain life in the Galápagos, one of the world’s most renowned marine ecosystems, and beyond.

“There’s nothing like seeing the Galápagos up close—the islands, the wildlife, the ocean currents—and knowing the data we collect here will help protect this extraordinary place,” says Claire Till.

This article was originally published on Oct. 1, 2025